FERTILIZER: A STORY

by Jeemes Akers

“The U.N. says Russia is the world’s No. 1 exporter of nitrogen fertilizer and No. 2 in phosphorus and potassium fertilizers. Its ally Belarus, also contending with Western sanctions, is another major fertilizer producer. The [Russia-Ukraine] conflict also has driven up the already-exorbitant price of natural gas, used to make nitrogen fertilizer. The result: European energy prices so high that some fertilizer companies ‘have closed their businesses and stopped operating their plants.’”[1]

One of the most lasting unintended consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine beginning in late February 2022—and subsequent Western sanctions on Russia—is an ongoing global shortage of fertilizers, particularly in the underdeveloped countries of Asia and Africa, that threatens normal food crops and could portend a global famine.

Let me provide one of many examples. A shortage of fertilizers is hitting Asian rice farmers particularly hard (prices of crop nutrients crucial to boosting rice production have doubled or tripled in the last year) and lower fertilizer use means smaller crops. As predictions of the International Rice Research Institute indicate, crop yields could drop by 10% in the next growing season, translating to a loss of 36 million tons of rice, or the equivalent of feeding 500 million people.[2] The Russia-Ukraine conflict has exacerbated rising fertilizer prices in this part of the world, already suffering from supply snags, production woes and disrupted trade patterns.[3]

Practically every plate of food makes it to the dinner table with the aid of fertilizers.

War-induced fertilizer shortages are becoming a part of a “perfect storm” threatening global crop production.[4] Even in our own country, where we traditionally blessed with fertile soil and abundant rainfall in the Midwest, a severe ongoing drought and fires have meant a smaller than normal spring wheat crop and, to make matters worse, many farmers will find it difficult to buy ever more costly fertilizers.[5]

As I started reading the many media accounts of global fertilizer shortages, I was reminded of my students in my many sections of History of Western Civilization II and one History of Modern Germany course at the College of the Ozarks. As most of these students would tell you (I hope), in my view of modern history, World War I stands out as the single most pivotal event: during the years 1914-1918, the countries of Europe committed mutual suicide; you can trace a trendline of steady progress and European domination up to 1914, but after 1918 (and the cultural, economic and political vacuum left in the wake of the collapsed monarchies), you can trace back every geopolitical issue plaguing us in our modern world.

Including synthetic fertilizers.

The development of modern (non-manure) fertilizers has four roots, all growing out of the backdrop of World War I: the necessity of coping with the onerous Allied naval blockade of Imperial Germany, the mobilization of science and scientists to serve the nation-state in a time of total war, the development of chemical warfare agents, and the genius of German chemist Fritz Haber (1868-1934).[6] Haber’s story—on one hand a tale of incredible scientific innovation, but on the other hand a tragic human story—is the subject matter of one of my favorite lectures stemming from the tumultuous Great Conflict, or as they called it at the time, “The War To End All Wars.”

At the onset of the war, Fritz Harber was one of a stable of incredible German scientists that dominated the era, a group that included, among others, Albert Einstein and Max Plank. Harber was born in Breslau, Prussia (now Wroclaw, Poland) into a well-off Jewish family. His mother experienced a difficult pregnancy and died shortly after he was born.

Like many of his contemporaries, Haber identified strongly as a Prussian and German, less so as Jewish.

Haber attended several prestigious German universities, receiving his doctorate cum laude from Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin in 1891 (today the Humboldt University of Berlin), having served his one-year military volunteer service obligation two years earlier with a well-known artillery regiment.[7]

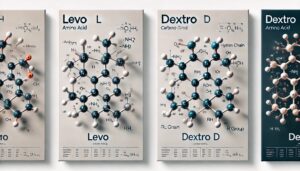

During Haber’s time at the University of Karlsruhe (1894-1911), he and his assistant invented the “Haber-Bosch process,” a method that synthesized ammonia from nitrogen gas and hydrogen gas under conditions of high temperature and pressure. Haber would subsequently win the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in inventing the process.

So, what is the big deal? Haber’s process was a milestone in industrial chemistry. The production of nitrogen-based products such as fertilizer and chemical feedstocks, were no longer dependent on ammonia obtained from limited natural resources (especially Chilean guano deposits) and could be produced from available and abundant atmospheric nitrogen. More applicable to our missive: the discovery led to large-scale production of nitrogen fertilizers. Even today, variations of this fertilizer process are still used as the food base by half the world’s population.[8]

Unfortunately, that wasn’t Haber’s only claim to fame.

Haber, like so many others throughout Europe, enthusiastically greeted the onset of World War I, joining 92 other German intellectuals signing the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three in October 1914.[9] Soon after the war began, Haber was promoted and headed the Chemistry Section in the Ministry of War. In this capacity, he assembled a team of more than 150 scientists and 1300 technical personnel.

As a result—historically speaking—Haber is considered “the father of chemical warfare” for his pioneering work in developing chlorine gas and other poisonous gases for use in trench warfare by the German military during World War I. As such, he was personally on hand when chemical gas was first released by German military during Second battle of Ypres (May 1915) in Belgium, resulting in 67,000 casualties.[10]

Less well known, Haber also helped develop the first generation of gas masks with absorbent filters. It was a different time and a different desperation. Gas warfare in trenches of Western Front was, first and foremost, a war of chemists.

By any definition, Haber was quite an extraordinary individual trapped by the exigencies of his nation’s survival in an age of total (and industrial) war. Or in Haber’s words: “During peace time a scientist belongs to the World, but during war time he belongs to his country.” Even after the war, Haber could not understand scientists like Albert Einstein who refused to identify with the German homeland. In a letter dated March 9, 1921, Haber proved almost prophetic in his warning to Einstein:

“Now is the moment in which adherence to Germany has a bit of martyrdom to it … For the entire world you are today the most important of German Jews. If you at this moment fraternize ostentatiously with the English and their friends, then people here at home will see that as a testament to the faithlessness of the Jews.”[11]

In the final analysis, Haber’s loyalty to his homeland came at a huge cost. Other global scientists shunned him after the war for his involvement in Germany’s gas warfare program. Even more tragically, his second wife, Clara Immerwahr, herself the daughter of a chemist, (she was also the first woman to be awarded a doctorate in chemistry in Germany), and a women’s rights advocate and pacifist, was reportedly so upset with her husband’s involvement in the chemical weapons program that she shot herself in the chest in May 1915.[12]

So, there you have it. Only an Akers’ missive (in five pages) would attempt to connect the dots linking today’s catastrophic fertilizer shortage, the current Russia-Ukraine “special operation,” the history-changing nature of World War I with its chemical warfare in the trenches, the genius of a German chemist, a tragic love story, and setting the stage for Nazi-era anti-Semitism. All of this, in turn, is but a small microcosm of the human experience carried on the unraveling scroll of history.

We need to start teaching history again …

[1] The Associated Press, “Russia-Ukraine war worsens fertilizer crunch, risking food supplies,” NPR, Apr 12, 2022.

[2] Pratik Parija, et al, “Rising Fertilizer Costs are Catching up to Rice Farmers, Threatening Supplies,” Bloomberg, Apr 18, 2022.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Michael Snyder, “Food Production Is Going To Be Substantially Lower Than Anticipated All Over The Globe in 2022,” The Economic Collapse, Apr 20, 2022.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For those interested in Haber’s role in scientific history, see (among others): Daniel Charles, Master mind: The Rise and Fall of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Laureate Who Launched the Age of Chemical Warfare, (New York: Ecco), 2005; Fritz Stern, “Together and Apart: Fritz Haber and Albert Einstein,” in Einstein’s German World, Princeton University Press, 2001; and, Dietrich Stoltzenberg, Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew: A Biography, (Chemical Heritage Foundation), 2005.

[7] Wikipedia’s article on Fritz Haber has a very good section on Haber’s education.

[8] Joerg Albrecht, “Brot and Kriege aus der Luft,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 2008.

[9] Siegfried Grundmann, The. Einstein Dossiers: Science and Politics—Einstein’s Berlin Period, 2005.

[10] Haber apologists will point out that his team of gas warfare specialists investigated the earlier use of Turpinite, an alleged chemical warfare weapon used by the French and their own Nobel laureate chemist Victor Grignard.

[11] Cited in Michael D. Gordin, Einstein in Bohemia, (Princeton University Press), 2020, p. 12. Gordin’s well-researched book is one of the best things I have read in a long time.

[12] See, among others, Bretislav Friedrich and Dieter Hoffmann, “Clara Haber, nee Immerwahr (1870-1915): Life, Work and Legacy,” Zeitschrift fur Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie, (Mar 2016) 642 (6): pp. 437-448; and, Susan V. Meschel, “A Modern Dilemma for Chemistry and Civic Responsibility: The Tragic Life of Clara Immerwahr,” Zeitschrift fur Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie, (Mar 2012), 638 (3-4), 603-609.