AL STAPLETON: A TRIBUTE

by Jeemes Akers

“A single rose can be my garden … a single friend, my world.”

Leo Buscaglia

Brenda left me a message on my phone yesterday (Wednesday, February 2, 2022) informing me that my best friend in high school, Charles Alvin Stapleton, had passed away. Al had asked her to give me a call when the end came.

“Sigh.”

I had difficulty sleeping that night. Dozens of memories of our mutual high school experiences flooded through my mind. I wondered how I could do justice to Al’s friendship. How can I appropriately honor Al’s memory?

Al never felt completely accepted at Springboro Local High School. He always considered himself an outsider of sorts. In many ways the rural hamlet of Springboro—located about halfway between Cincinnati and Dayton—was the ideal place to be raised in the 1960s. But every paradise has its warts. At school there was a definite, but subtle, social pecking order of “ins” versus “outs.” It was not about money. Nobody said anything in public—they didn’t need to. The established town families (and their children who had attended school since elementary school) had a very nuanced sense of elevated status that manifested itself against those people who moved in later.

It is difficult to explain. I witnessed the same sort of dynamic unfold elsewhere: a hidden cultural snobbery—a defined sense of “insider” versus “outsider—in the Appalachian mountain culture of eastern Kentucky.

At any rate, among those moving in later to our small town was the Stapleton family, living in a two-story house off Catalpa Drive in the new Royal Oaks section of Springboro.

We also lived in Royal Oaks, moving there during my ninth-grade year. But I managed to straddle both sides of this cultural divide. My dad was born near the town, and attended Springboro’s schools all his life. Indeed, outside of a very short stint in the U.S. Marine Corps during the closing years of World War II, dad had has always lived within a radius of twenty miles from where he was born. In addition, our family attended a church in town. Moreover, I had attended First Grade at Springboro and we returned to town—living in the Pence House in the old part of town—starting in the sixth grade.

Al’s dad—Charles—worked for Dayton Power and Light and his mom worked at Delco Moraine in Moraine City. In those days, many of the dads of our schoolmates worked in companies located in Dayton, such as National Cash Register (NCR)—at one time a sprawling industrial complex of buildings (in my childhood years, NCR would host Christmas shows and had a wonderful swimming pool for the community. What happened? A technology shift to digital and, quite honestly, excessive union demands. Today, there is a small museum and most of the property is controlled by the University of Dayton). Even the massive DPL power complex that Al’s dad worked at is gone: you can still see the remains when you approach the outskirts of Dayton on Interstate 75. Speaking of I-75, it was built during our high school years and greatly reduced to time getting to-and-from work for Springboro-based families.

I loved spending time at Al’s house: it was like my second home. Al had an older brother Eddie (better known as the dungeon master at the Renaissance Festival near Waynesville) and a younger sister Nancy Kay: they were part of my extended family.

With Al’s passing, all of the Stapletons are now gone. His mom died early, during our high school years. A few years after she passed, Charles would move with the kids out to a place off Pennyroyal Road.

I have wonderful memories from those years and many include my sidekick Al. Those were the days of the British music invasion and everybody collected the songs of their favorite groups. Some, of course, collected Beatles music. And by music collections, I mean 45 rpm records or 33 rpm albums—plastic was the technology of the day. Al’s favorite British group was the Searchers (named after a John Wayne movie). Indeed, the song “Needles and Pins” remains one of my favorite songs to this day, and I still listen to 60’s music on SiriusXM when I travel. I collected, by the way, the records and albums of The Dave Clark Five (the song “Glad All Over” broke the Beatles stranglehold on songs at the top of the music charts).

The British music invasion had other cultural spillovers. Instead of the Brylcreem-induced ducktail look, everybody grew their hair longer. Me included.1

Both Al and I were ornery during those years. (And that is the understatement of all understatements!) Al’s dad allowed him to drive the family 1954 cream-and-black Chevy station wagon. I have a lifetime of stories from those trips we took together with Al behind the wheel. We were all young, naïve and convinced we would live forever. Classic knuckleheads! Squeezed into the Stapleton-wagon, we would go to climb bridges, knock down mailboxes in the countryside and pitch firecrackers outside. One of my best-ever practical jokes happened inside Al’s station wagon. We had bought a bag full of cherry-bomb firecrackers. We delighted in tossing them outside. One of the fuses worked its way loose from a cherry-bomb at the bottom of the bag. I lit the fuse, yelled “look out” and tossed the sparkling fuse into the crowded back seat. They scrambled like ants in the back, clawing over each other to escape the blast. Al was driving and laughed loudly, as did I in the passenger seat. Needless to say, our comrades in the back seat didn’t think it was nearly as funny.

Al’s station wagon (or his dad’s) came to an inglorious end. As usual, we were all crammed into the vehicle. On Weidner Road, outside town and just past the graveyard, was a huge hump in the road. When Al floored the station wagon and hit the hump just right, we would go airborne for the briefest of moments. Our stomachs would respond with a fluttering sensation. That’s exactly what happened on one bitterly cold winter evening. But something went wrong with the script. When the station wagon landed, we all heard a strange sound and the drive train broke, digging deep into the tar-and-gravel covered road. We went from warp speed to zero in an instant. All of us were thrown headfirst into the windshield (it was before seatbelts became mandatory).

As a result, we were forced to walk several miles back to town, with howling winds whipping at our heels at every step, each of us trying to make up a story that Al could tell his dad to explain the calamity.

One night after our Explorer Scouts meeting, a handful of us began to walk uptown. Al and I were among the group. I don’t know what possessed us. A couple of us—me included—picked up a handful of rocks and pelted a nearby stop sign, at the same time shouting out at the top of our voices. Then we scattered like a bunch of startled starlings. Did I mention that Springboro was a really small town? The local police quickly rounded us up, Al and I included. We were interrogated like hoodlums at the local police station. Among our number was a teenager that had run afoul of the local law enforcement officials on several occasions. Al and I got off with a threat to tell our respective fathers if we were ever there again.

The threat worked for both of us!

Al and I both were members of the local chapter of the Explorer Scouts (for boys aged 14-18). Our group was led by Johnny Sortman’s dad and a kind-hearted fellow named Bill. They were far more serious about the scouting process than either Al or I. As I recall, the highlight of the experience was a couple money-raising projects: the first was working with a local apple orchard owner to bottle apple cider which we planned to sell for profit—something went wrong and we ended up almost giving away the bottles as vinegar. The second was going down to the Stapleton farm (near Jackson, Ohio) and cutting down a truck full of Christmas trees. The trees were so scrawny (Charlie Brown’s Christmas trees would be like the White House tree by comparison) that we ended up throwing most of them away.

But at least there were the scouting jamborees. We would show up, pitch a tent and bring the food to the camping site. Most of the other attendees would busily engage themselves in classes to earn merit badges. Our crew pursued a different tact: we stayed inside the tent and played cards.

Al Stapleton was a cardplayer par excellence. Name the game and he played it: poker, rook, pinochle, euchre, hearts or spades. I remember one outing at the Stapleton cabin on their property near Jackson. We played a game of poker with a different twist. When a player ran through his chips, they had to take off all their clothes and run around the house buck naked. It was a cold January night, by the way.

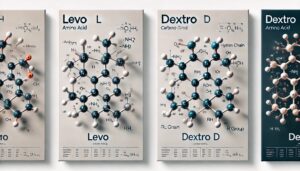

After high school, Al attended the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terra Haute, Indiana—a premier engineering school back in the day—for a short time. Al had a really sharp mind when it came to engineering and the like—in later years, he attended and maybe taught classes at the newly established Wright State University. Brenda said that Al instructed his body to be left to the Wright State medical facility—“so it can help others.” That is classic Al Stapleton: no funeral service, no fuss and commotion, no elaborate post-death ceremony.

But I am getting ahead of the story. Those years after high school were the days of the draft and the Vietnam War. Al enlisted in the U.S. Air Force.

Al was one of two friends I know that walked away from a catastrophic plane crash. I tell the story in my missive Ray, Al and Mom’s Restaurant:

“My best high school friend, Al Stapleton, doesn’t eat at Mom’s Restaurant all that much. He is more of a loner these days. Al is also a Vietnam veteran. He also enlisted in the USAF. He was on his way to Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam, aboard a military-contracted DC-8 jetliner on November 27, 1970. The aircraft crashed at the end of the icy runway in a fireball after a refueling stop in Anchorage, Alaska. The aircraft broke into three parts nearly three-quarters of a mile from the runway’s end. Of the 229 passengers, 46 died in the flames (45 military personnel and one stewardess).

Al told me that a subsequent investigation revealed that—for some reason—the aircraft’s parking brake was left on. All the tires blew out. Al could see one of the engines on fire as the plane roared down the runway.

He knew they were in trouble.

The pilot tried to abort the take-off.

But it was too late.

Al was one of the survivors of the crash. All the passengers seated in the rows behind him died. His seat was hurled clear of the airframe by the force of the crash and explosion. He remembers the flames, struggling to free himself from the seatbelt, helping someone else get out of their seat belt and putting out the flaming uniform of another soldier with his hands.

He doesn’t know their names.

Al refuses to fly again.

Understandably.

This week was the first time—in all these years— that Al shared some of the details of that fateful day.

I have never asked before.

Al was transported to the premier military burn treatment center in the country—Brookes Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. He was in recovery for over six weeks. They didn’t have artificial skin to treat burns back then. Instead, patches of pig skin were grafted on burn areas with the hope that normal skin cells would attach themselves to the patches and grow normally. During those weeks of painful recovery, Al came and visited me at Lackland AFB in San Antonio where I was in basic training.

I’ll never forget that.”

In my eyes, my good friend Al Stapleton is a true hero.

And should be remembered that way.

The plane crash and the military experience changed Al. He went from being the life of the party (even in later years he was a fantastic disco dancer) to becoming much more serious and insular. He became jaded when it came to the American dream: a job in corporate America, a house (mortgaged to the hilt), and a family (Delores went back to California and he lost track of his son).

Thank God Brenda M. stepped into the void. For the last several years they lived together in a small frame house off Route 73 heading toward Waynesville.

In the latter years, Al plied himself at woodworking (and he was very skilled) and for a time, volunteered at the Pioneer Village near Caesar’s Creek Lake. I tried to keep in touch during those years, especially when I came into Springboro to visit my parents. On occasion, Al would come by the house on Royal Drive to play a game of cards in the kitchen.

The last time I saw Al was at a veteran’s meeting in Middletown, Ohio (the Veteran Social Command). The sicknesses, chemotherapy and medicines had ravaged his body: he was thin, gaunt, and a mere shadow of himself. Even then, Al didn’t complain. Brenda says that the thing he enjoyed most in those final sickness-ridden years was spending time with that group of veterans. He worked tirelessly with the group to help ensure veterans obtain their full benefits from the Veteran’s Administration.

Long gone now is the pine tree Al and I planted on one side of our house on Royal Drive: dad was suffering from a severe back injury at the time. Al and I managed to scratch out a hole in the frozen ground and planted the live tree which our family had used as a Christmas tree that year. It was a miracle that the tree survived: eventually it grew so big that it interfered with the power lines on that side of the house and had to be cut out.

Just like the tree, Al has been cut out of my life. If I would mention all the times we laughed together, cried together, listened to music together, avoided death in near car wrecks together, talked about God together, and conversed about the girls in our life together … this missive would be at least 50 pages long.

“Sigh.”

I just can’t imagine what it would have been like to navigate the tsunami waves, eddies and vicissitudes of life as a teenager without my close buddy Al.

I will miss him dearly.