WHY I LOVE ART

“It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.”

Henry David Thoreau

Those of you who know me best know how much I love art. I love the whole process: from the initial mysterious creative impulse, to putting pen and brush to paper or canvas to breathe life and form to the idea, to completing the final product and, best of all, to the emotive response by those looking on the finished artwork for the first time. I know from my personal experience that each of my own pieces of art contains a flaw—a mistake—so that it becomes my task as creator of the artwork to cover, or blend in, the blemish so it becomes unnoticeable to the observer. When viewing the artwork later I notice the flaw and how it was corrected, even when no one else does. In that way, the whole process of art reminds me of our Heavenly Creator, the ultimate artist: he takes each of us as a fresh canvas—despite the mistakes, warts, and blemishes that unfold as the work proceeds—and eventually shapes us (if we are willing) into a beautiful work replicating His perfect Son.

This missive deals with four pieces of art that have played a special role in my life. There are, of course, many others. I hope you enjoy.

Yesterday, I decided to begin a task that I have been avoiding. Left over from our house move over a year ago—and tucked away in a corner of guest bedroom in our temporary apartment—is a box containing a collection of pocket-size notebooks, hand-written notes scribbled on everything from Subway napkins to small corners of papers and a mishmash of other memorabilia. What a treasure trove of memories!

Trying to digitalize and bring some sense of order to this disparate collection, however, has proved to be a real challenge.

During this process I stumbled across a notebook containing my personal observations compiled during a trip to Germany in August 1986 with my sister Debbie. It was the experience of a lifetime! My purpose for the trip was to gather additional information for a biography of the colorful, dashing and controversial Ussuri Cossack military officer General Prince Pavel Rafalovich Avalov-Bermondt (1877-1974). Avalov-Bermondt was one of millions of tragic figures set adrift by World War I’s traumatic convulsions that resulted in, among many other things, the collapse of centuries-old dynasties: Hohenzollerns in Germany, Hapsburgs in Austria-Hungary, Ottomans in the Middle East and Romanovs in Russia.

In my World History courses I point to the First World War (1914-1918)—the “War to End All Wars”—as modern history’s most important pivot point: all threads of European world domination logically progressed to 1914; likewise, all our present-day global problems can be traced back to 1918. Among those displaced individuals who refused to accept the new post-war world order was Avalov-Bermondt. His life’s journey placed him at the scene of the most momentous events of the early twentieth century: he fought in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), fought in World War I, was an eyewitness to the revolutionary events unfolding in St. Petersburg that toppled Tsar Nicholas II (1917), led a “White Army” against the Bolsheviks in the Baltic during the Russian Civil War (1917-1923), and emigrated to Weimar Germany where he organized a Cossack-Ukrainian proto-Nazi party. After Hitler’s invasion of Russia he had little use for Avalov-Bermondt; indeed, when I was in Germany I was convinced that he had vanished in a Nazi concentration camp (subsequent research has traced him to New York, where he is buried in a Russian Orthodox Cemetery in Nanuet, New York).

Back to my notes of the research trip. I attempted to retrace Avalov-Bermondt’s trail across Germany some 60 years later, but it was a difficult task. Besides the trail getting cold over time, to make matters worse, Germany was still divided and the Cold War was in full swing. Pausing my quest, my sister and I visited the Bavarian cultural capital of Munich and the nearby Dachau concentration camp (opened by the Nazis in 1933).

What a sobering experience!

Dachau was technically not a death camp, at least initially, but a work camp. We walked through the large metal gates signifying Arbeit Macht Frei (“Freedom Through Work”). You could sense the spirit of death inside. We toured the barracks, ovens, buildings and exhibits, but my attention was captured by the International Monument topped by what appeared to be—at a distance and from my vantage point—a modern art “mess” (from my notes). Then the closer I got, the more the sculpture made sense. The monument was designed by Nandor Gild, a Yugoslavian artist and concentration camp survivor. As one travel guide notes: “His sculpture conveys fence posts, barbed wire and human skeletons. The human figures depict those who, in acts of desperation, jumped into the barbed wire to end their suffering. The instant someone ran towards the fence they were shot by SS guards.”[1]

From my notes: “It was the single most effective piece of art I have ever seen.”

(Interestingly enough, as I write this missive, four friends remain quarantined in Munich for Covid-related reasons and hope to be able to fly back home in a few days. Traveling abroad incurs special risks these days).

Curled up on the main portion of my roll-top desk (bought with my Vietnam War bonus from the state of Ohio), is a reproduction of a painting displayed in the Australian War Memorial located in the suburbs of Canberra, Australia. The Memorial is one of the world’s great military museums. Particularly impressive is the west wing’s First World War collection, consisting of creative and evocative dioramas, realistic wartime exhibits and, of course, artwork.

It is difficult to overstate the influence of World War I—particularly the ill-fated Allied Gallipoli Campaign (1915-1916)—on the Australian psyche. 8,609 Australians lost their lives during the campaign (out of a total wartime loss of over 60,000 lives—out of a total estimated population of 4 million; at a casualty rate of over 68%, the proportional losses were among the highest of any participating country). I have been in Australia for celebrations and ceremonies on ANZAC Day (April 25), the national day commemorating the country’s war dead.

There is nothing quite like it in our country.

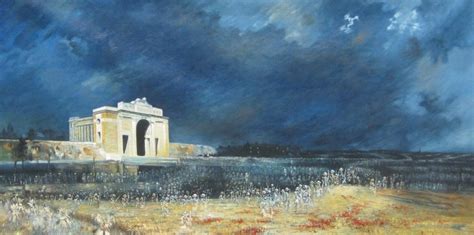

At any rate, tucked away in an alcove of the Memorial’s west wing was a large painting (over four feet x eight feet in size) that I will never forget. Australian artist Will Longstaff’s Menin Gate at Midnight, painted in 1927, is a haunting piece of art that depicts a host of ghostly soldiers marching across a field in front of a war memorial in Belgium. The lighting in the alcove perfectly enhances the eerie, ghost-like band of soldiers. The artist was said to have seen a “vision of steel-helmeted spirits rising from the moonlit cornfields around him.”[2]

His finished artwork certainly reflects the power of the vision.

I have talked about the third artwork in the past. As I wrote in my missive “Sweatin’ at Shwedagon”:

“The eye-popping lobby of the Erewan—one of the grandest hotels in the “City of Angels” [Bangkok, Thailand]—features at the far end a majestic staircase guarded by two huge, carved stone, black elephant sentinels. The impressive marble stair-well leads to elaborately decorated floors above.

Hovering, almost lifelike, over the staircase’s first landing is a gigantic painting. I mean the type of artwork that takes your breath away. Vibrant colors—especially the reds and golds—depict a variety of Asian landscapes populated by scores of humans and supernatural creatures. But what attracts me, every time, is the artist’s rendition of a giant spiritual “zipper” separating, at various junctures, the physical world from the world beyond our perception.

That piece of artwork best captures, in my mind, the essence of the mysteries of Buddhism. It sums up, in one larger-than-life canvas, the incredible visual and spiritual experiences of places like the Shwedagon Pagoda [the ancient Buddhist religious site in Yangon, Myanmar].

The artwork is magnificent.

And unforgettable.

I always leave the place wanting to capture—with my own artistic rendition—the separation of this world and the glorious vision of New Jerusalem and the Kingdom to come.

Sigh.”

I can’t improve on that.

The fourth artwork I would like to mention is my own. It is my personal favorite of all the things I’ve done. I certainly don’t mean to compare my own meager efforts with those celebrated artworks mentioned above. Of course, there is no comparison. But it is my missive after all and one of my favorite art-related stories. The artwork I am talking about is a pen and chalk rendition—with just a splash of red—of a fierce-looking Chinese dragon.

Many of you have seen it.

It was my last week at the embassy in Singapore. Hidden in the shadows of the high-rise glass and steel behemoths of the city-state’s Central Business District is a small cluster of Taoist temples dating back to the early nineteenth century. I particularly liked to visit one of these because inside—amid the pungent smells of incense and burning papers—were two incredible, intricate stone carvings: a dragon on one side, a tiger on the other.

I was determined not to leave Singapore without obtaining an image of the dragon.

To that end, I entered the temple carrying my camera and an art pad. I asked the monk and keeper of the temple if I could take a picture of the dragon. “T-s-k-k, I don’t know,” he said politely (in Asia many believe that taking a picture of a person or thing somehow robs it of its spiritual essence).

“I understand,” I replied, “would it be permissible for me to sketch the carving?”

Obviously, no one had asked him that. “I guess that would be okay,” he said as he stroked his long white chin-whiskers, no doubt pondering the other-worldly ramifications of his decision.

So, I sat there armed with my trusty art pad and pencils, in front of the huge, imposing, fierce-looking dragon stone carving. I began to draw. From time to time, one or two temple patrons would drift by, look over my shoulder to study what I was doing and grunt their approval.

I was still drawing as the first whispers of dusk enveloped the outer temple compound decorated with its festive red lanterns.

Finally, assisted by the light provided by the temple’s many candles, I applied the finishing touches to my drawing. It had taken me almost all day. As I closed my art pad and prepared to leave, I approached the monk. “You have been so kind,” I said, “I would like to leave a small donation for the temple.”

“You don’t have to do that,” he said with a smile. Then looking over both shoulders to make sure no one was watching (no visitors had been in the temple for at least two hours), he whispered “you can take a picture of the dragon if you won’t tell anyone …”

In Asia, it has been my experience, that a well-intentioned and well-timed gesture of generosity (especially of money) can melt down the deepest-rooted traditional, cultural and institutional barriers. My sole regret, as I shuffled away from the temple, was that I hadn’t offered the donation earlier in the day.

[1] Rhonda Krause, “Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Tour—Remembering the Past,” Travel? (n.d.); accessed through Wikipedia.

[2] Anne Grey, “Menin Gate at Midnight.”